Ten months into the pandemic, California school districts are struggling with whether to reopen classrooms as public health experts warn that the risks of returning students to class might be outweighed by the harms of keeping classrooms closed.

Frustrated parents, politicians and health experts say that too frequently, politics rather than science determines which children are now in classrooms learning in person and which are still sitting in front of a computer.

So far, federal and state officials haven’t dictated when and how schools should reopen, passing the call to local county health officials.

While counties use science and data to guide reopening the economy — case counts or available hospital beds are factored in — pressure from the community and local unions often influences California districts’ reopening decisions.

It is up to each of California’s 1,000 school districts or each private or charter school to decide whether to bring students back.

Sending students and staff back to schools will likely mean more coronavirus cases. Some teachers, parents or children could die. The concern is even more pressing now, as cases surge across the country and California orders new pandemic restrictions.

Yet, distance learning has devastated many students and families, leading to academic, physical, emotional and social setbacks that could take years to address. The achievement gap is widening, absenteeism is surging, and the well-being of more than 6 million children is at stake.

A paper published this month in the medical journal JAMA Pediatrics found that the school closures could reduce educational attainment and life expectancy among children, with a projected 5.53 million years of life lost in the United States.

Increasingly, education leaders and other public officials are calling on Gov. Gavin Newsom to provide guidance on reopening schools, with specifics on how often teachers, staff and even students should be tested.

They would also like the state to set the conditions for reopening, based on local case rates and other quantitative data. If those conditions are met, schools would open, said Morgan Polikoff, University of Southern California associate professor of education.

So far, such specificity has been reserved for hair salons and tattoo parlors, but not schools.

Even in the middle of the current surge, counties in the most restrictive purple tier can still open schools. Dozens of Bay Area private schools have reopened in recent weeks, as have a handful of public districts like Manteca in the Central Valley and Bel Aire Elementary in Tiburon, with many more planning to bring students back starting this month, including Palo Alto, Mill Valley and Burlingame.

Others have announced they won’t reopen until at least after the winter break, including San Francisco and Oakland.

“There is pressure to reopen, but it’s not evenly distributed,” said Polikoff. “We’re letting these elected (school) boards, who don’t know anything about science ... make those decisions.”

In some places across the country, including the Bay Area, local communities have reopened bars and restaurants, which are arguably higher risk, before schools. That has potentially led to outbreaks and higher case counts, which then increases pressure on schools to stay closed. That concern has sparked social media uproar, including the Facebook group Schools Before Bars, which has more than 5,000 members.

In contrast, countries in Europe including Germany, France and Ireland have responded to case surges by closing bars, restaurants, theaters and gyms, while keeping schools open.

“Every single country except this one, they have prioritized school opening and children first,” said Dr. Monica Gandhi, an infectious disease expert at UCSF, saying that is a moral failing of school leaders — including those in San Francisco. “They’re not representing the principles they always profess to possess — the needs of the poor, the needs of the working class.”

In California, however, labor unions also have a significant say in the decision, requiring agreements on working conditions and pandemic protocols to return, but that means the state’s 1,000 school districts must each collectively bargain with unions on when and how to reopen rather than using a single, coherent, evidence-based strategy directed by state officials, Polikoff said.

It’s a recipe for not reopening, he said.

In many communities, the debate is fierce, with some saying the risk of even one case, one death is too great to reopen schools. That’s been the case in San Francisco, where until this week, the school board hadn’t put a timeline on reopening, despite intense pressure from many parents and the mayor.

Parent Dheyanira Calahorrano, with an 11-year-old at Everett Middle School, wants San Francisco to reopen classrooms now. “This situation is already crazy, it's too much,” she said. “It’s already two months and a half. By now we know distance learning is not working.”

Some San Francisco school district employees still have concerns about whether it’s safe to return.

“Collateral damage is unacceptable, so we need to take the time to get things right and avoid a human casualty,” said Joan Hepperly, executive director of the United Administrators of San Francisco, which represents district principals, among others. “We want all administrators, staff, students and community members to be safe as we open schools in person.”

That includes proper ventilation, a testing schedule for staff and more, Hepperly said.

“We do want kids back in school. We want the schools open,” she said. “We want everything in place to minimize anybody getting COVID.”

Yet the reality is that there is no “safe” in a deadly pandemic, and it’s devastating to keep schools closed given the devastating academic, health and social impact of distance learning on too many children, Gandhi said.

Education officials aren’t trusting the science or their health officials, she said, but she added that the risk to teachers and staff is “minimal, with proper precautions,” and teachers and school staff are essential workers.

In Oakland, district officials have opened school-based hubs, bringing in staff who volunteer for in-person support, as well as after-school providers and other staff to work with high-needs students struggling the most with distance learning. But the district doesn’t plan to reopen classrooms until January at the earliest.

With the pandemic surging, some counties have paused the reopening of some schools, while allowing those that already have started in-person learning to continue.

On Tuesday, the California Federation of Teachers called on public schools to shut down or remain closed until at least January.

“Our focus has been and will remain on ensuring that all students, school employees and community members are safe,” said Jeff Freitas, president of the labor union, in a statement. “With cases on a dramatic rise, taking decisive action now, rather than waiting for the last moment, is the right move.”

For public health officials, however, determining what to close and what to keep open is a data-driven decision. The main goal is not to eliminate cases, but rather to keep them low enough that hospitals will not be overwhelmed with patients, crushing the health care system and leading to preventable deaths.

With the pandemic’s third wave hitting the country, public health officials hope to avoid another shelter-in-place order like in March. In New York, officials are considering closing schools that only recently reopened as cases quickly climb after a long period of relative calm.

San Francisco has had one of the lowest death rates and case counts in the country for large urban areas: 1,585 cases and 18 deaths per 100,000 residents.

County health officials started allowing schools to reopen in September and have said they can remain open even as other activities, such as indoor dining and religious services, are shut down amid recent increases in cases. But San Francisco public schools have remained reticent, with labor unions and district leaders questioning the safety of students and staff.

By comparison, San Joaquin County has had 3,241 cases and 68 deaths per 100,000 residents.

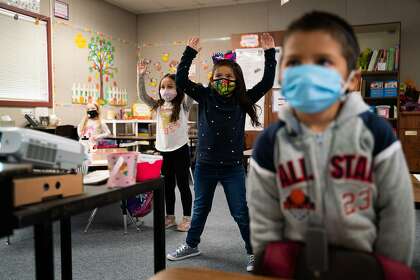

Manteca Unified opened earlier this month, starting with the youngest students as well as high school seniors and juniors, with a hybrid schedule reducing class sizes.

District officials said it was critical to bring students back, acknowledging they fully expect cases of coronavirus among students and staff, and they are tracking those cases on a public database.

In recent weeks, San Francisco city officials and many parents have increased the pressure on district officials to focus on reopening, setting dates and increasing the urgency to assess facilities and ensure protocols and resources are in place.

On Tuesday, the board unanimously voted to set the date of Jan. 25 for students to start returning.

“The continued closure of our public schools is hurting our kids and our families, and we need to do everything we can to safely get them open,” Mayor London Breed told The Chronicle.

It’s incumbent on state leaders to take a stronger role in directing the reopening of schools, taking some pressure off local districts to make the difficult decision of whether to reopen, experts said.

“Somehow during the pandemic, schools have been an afterthought,” said Joseph Allen, professor of public health at Harvard University. “Some districts are staring at the prospect of being closed through the winter. I don’t think people are grasping just how devastating that is.”

Jill Tucker and Erin Allday are San Francisco Chronicle staff writers. Email: jtucker@sfchronicle.com, eallday@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @jilltucker, @erinallday

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "In California, science guides whether to reopen hair salons — but not always schools - San Francisco Chronicle"

Post a Comment